Innocence vs. Experience

William Blake (1757-1827) was a poet, printer, painter, and visionary, by which I mean he saw visions of angels and other spiritual beings. His work was not popular during his lifetime: he printed his own poems, which were illustrated with his own engravings, and then painted the finished projects with watercolors.

He’s most famous for the poems from Songs of Innocence (1789) and Songs of Experience (1794), but he also produced such works as the prophetic poems Visions of the Daughters of Albion (1793), Milton (1811), and Jerusalem (1820).

While Blake is a religious poet, his religion is rather unorthodox. His poems create a kind of rewrite of Biblical stories and themes. For Blake, the central religious story is the fall into division, the separation of humanity from God, and the redemption of humankind through imagination. According to one critic, “In Blake’s theology, we achieve redemption by liberating and intensifying the bodily senses and by attaining and sustaining that mode of vision that does not cancel the fallen world but transfigures it, by revealing its eternal imaginative form.”

Blake is intensely opposed to reason and science, which he sees as diminishing human experience, and intensely committed to passion and emotion. Like many Romantic thinkers, he dislikes the God of the Old Testament, whom he sees as tyrannical and emotionally distant, and believes rebellion against such an authority figure to be a noble act.

In the poem “Mock On, Mock On, Voltaire, Rousseau” (Norton 788), we find Blake’s statement of at least some of his principles:

The Atoms of Democritus

And Newton’s Particles of light

Are sands upon the Red sea shore,

Where Israel’s tents do shine so bright.

The reason Blake dislikes science and reason is that they reduce the world to nothing but its material components—reality is made of atoms, and nothing else. In this stanza, Blake is saying that there’s more to reality than just the physical—there’s also a spiritual reality, which he presents as Israel’s tents on the Red Sea shore. This reality is supremely more important than material reality. We need to remember we’re living in a spiritual, Biblical age, and one of Blake’s complaints about science is that it blinds us to that spiritual reality.

There’s a similar theme in “And Did Those Feet,” which draws on the legend that Jesus somehow came to England during his earthly ministry. Blake uses that compelling thought—did Jesus really come here?—to express how he sees contemporary England.

Did the Countenance Divine

Shine forth upon our clouded hills?

And was Jerusalem builded here,

Among those dark Satanic Mills?

The final stanza of the poem expresses the reality that Blake wants to see:

I shall not cease from Mental Fight,

Nor shall my Sword sleep in my hand,

Till we have built Jerusalem

In England’s green & pleasant land.

Again, Blake is presenting the idea that the spiritual, Biblical age is not over. We need to live our lives as though Jesus is still walking in England, as though we’re still living in the Biblical age. We need to make spiritual reality our reality and recognize that we can, symbolically, build Jerusalem in England. The scientific explanations of reality have failed, because they’ve led only to “dark Satanic Mills”—not just the factories that have taken over England in the Industrial Revolution, but also modes of thinking that deny the life-giving message of the Bible. By changing our way of thinking about reality (“Mental Fight”), we can build a new, spiritually-based England.

It’s important to recognize that Blake’s perception of science is influenced by the changes the Industrial Revolution have brought to England: factories belching thick coal smoke, child labor in the textile factories, long hours for starvation wages (no weekends off, either), people left homeless as landlords figure out it’s more profitable to tear down cottages on their land and raise sheep, urban overcrowding as displaced people flock to cities, cities that overcrowding and pollution have rendered filthy and squalid. It’s no wonder he longs for a change.

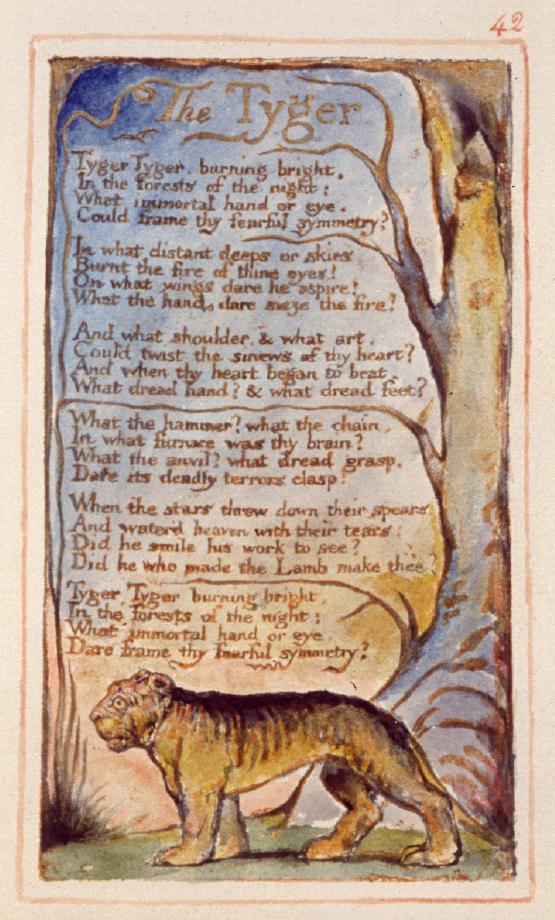

When we look at Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience, we can certainly see some of the same concerns. Often, a poem from Songs of Innocence match up with a poem from Songs of Experience, and it’s not hard to pick out Blake’s criticism of industrial society. For example, “The Lamb,” from Songs of Innocence, has a rural setting (“By the stream & oe’r the mead”), whereas its companion from Songs of Experience, “The Tyger” is described in mechanical and industrial terms (“What the hammer? what the chain?/In what furnace was thy brain?”).

There are other differences between the poems as well. “The Lamb” has a sing-songy rhythm and repetitive (“Little Lamb, who made thee?/Dost thou know who made thee?”); a number of students have compared it to the kind of poem you would read to a child at bedtime. “The Tyger” has more of a driving rhythm and isn’t nearly as repetitive. “The Lamb” begins with a question in the first stanza—Who made thee?—and answers that question in the second stanza—Jesus made thee. “The Tyger” is really just one question after another

Another difference between the two poems has to do with their presentation of the Creator. “The Lamb” makes the statement that we can know something of the lamb’s creator by looking at the lamb: “He is called by the name,/For he calls himself a Lamb:/He is meek & he is mild,/He became a little child.” When we turn to “The Tyger,” however, we find Blake has complicated the issue. If looking at the lamb tells us the creator is meek and mild, what does looking at the tiger tell us about the creator? “Did he smile his work to see?/Did he who made the Lamb make thee?” What kind of God could make the dark, mechanical, deadly tiger?

It’s also interesting to look at the pair of poems, each called “The Chimney Sweeper,” from Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience. They’re both referring to the same social reality: parents would apprentice their young sons to chimney sweepers for a fee; the chimney sweepers would lower the kids down the narrow chimneys so they could clean the soot and creosote deposits. It was a dangerous occupation: many of the boys died of suffocation or broke bones or contracted tumors and diseases as a result of their exposure to the toxic chemicals in the chimneys. “The Chimney Sweeper” from Songs of Innocence has some unhappy parts—the speaker’s mother dies in the first line and his father sells him into this apprenticeship, Tom Dacre cries because his head has been shaved—but its end is hopeful. Tom has a vision of an angel releasing all the chimney sweepers from their coffins and sending them off to play in heaven’s clouds; it ends with the lines, “Tho the morning was cold, Tom was happy & warm;/So if all do their duty, they need not fear harm.”

“The Chimney Sweeper” of Songs of Experience contains no such hope. Instead, from beginning to end, it condemns not only the parents who sent the child off to work in the chimneys but also the government and the church as well:

“And because I am happy, & dance & sing,

They think they have done me no injury,

And are gone to praise God & his Priest & his King,

Who make up a heaven of our misery.”

“The Chimney Sweeper” of Experience blames not only the parents who sold the child into this deadly apprenticeship but also the king and the priest who allowed it to happen. People may talk about industrialization bringing prosperity, but in this poem Blake seems to be making clear that only certain people profit. The parents and the priest and the king live in a kind of heaven, but at the expense of these poor, exploited children.

Many readers see “The Chimney Sweeper” of Innocence as making the same point, stating that Blake is presenting the chimney sweepers as being tricked by the church, which teaches them that if they do their duty, their suffering will be rewarded in heaven. Certainly, according to Biblical standards, the church should be in the business of proclaiming justice and alleviating suffering on earth; instead, even the poem in Innocence presents the church as working to insure that injustice will continue.

One way to interpret Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience is to see innocence as being associated with ignorance and naiveté, and experience with wisdom and reality. Many Romantic thinkers celebrate innocence and childhood, because they see experience as degrading and corrupting: the older people get, the less fresh and spontaneous and emotionally open they become. It’s hard to reconcile this view of the poems with Blake’s visionary agenda, however. Instead, Blake would probably see experience as something to be overcome with imagination and passion and spiritual insight. The pain and suffering and darkness presented in Songs of Experience should not be ignored, but we shouldn’t take them as any kind of final truth. Instead, they should spur us on to the Mental Fight as we work to build Jerusalem.

For discussion:

- What differences do you see between the poems presented in Songs of Innocence and Songs of Experience? What ideas or values does Blake seem to be presenting in the poems I haven’t discussed in this post.

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home