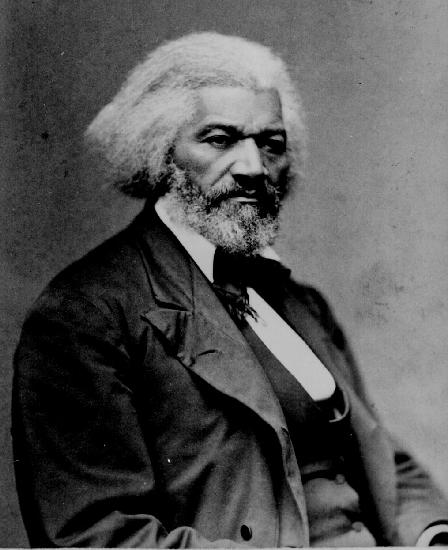

"The African-American Ben Franklin"

Frederick Douglass (c. 1818 – 95) wrote Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave (1845), in order to correct false impressions. Prior to its publication, he had worked for the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society for four years, giving lectures about his experience as a slave and speaking against the evils of slavery. One of the criticisms leveled against him was that he was too well-spoken—people doubted he had ever really been a slave. He writes Narrative, then, at least in part, in order to give his background, to demonstrate that he knew the atrocities he spoke of first hand.

After Narrative was published, unfortunately, Douglass’s owners became aware that heir escaped slave was living in the North, and Douglass’s friends and supporters began to worry that he would be kidnapped and taken back to Maryland to resume his life of slavery. To prevent this, Douglass spent two years touring Great Britain, giving anti-slavery lectures there, until his friends were able to raise the money to purchase his freedom from his owners.

Douglass’s Narrative is the best known and most highly regarded of hundreds of slave narratives that were published in the nineteenth century. The purpose of writing a slave narrative is to expose readers to the abuses of slavery—most detail the suffering the author has gone through: physical abuse, sexual abuse, having parents or children or spouses taken away when they’re sold to distant owners. Most end with the author’s escape from slavery to the freedom of the North.

One of Douglass’s purposes in writing the Narrative was certainly to convince his readers that slavery was evil and to counter the arguments that defenders of slavery had made. The second sentence of the Narrative presents slave owners as pettily refusing to let slaves know their ages (Norton 923); Douglass points out the ridiculousness of this practice and uses it as a symbol of one of his main points in the book, that slave owners want to keep their slaves ignorant, even if there’s no practical reason for them not to have that knowledge.

A couple of paragraphs later, Douglass begins to talk about the sexual abuse that pervades the slave experience, revealing that his master was his father; he goes on to consider the consequences of that fact, speaking of the perversity of fathers standing by while their white sons beat their black sons (924), and raising the question of whether or not this mingling of the white and black races will have any effect on the arguments of people who claim that black people are slaves as a result of a curse Noah placed on his son Ham in Genesis—how much white ancestry does a person need for that curse to no longer apply?

Many of the passages in the Narrative take a similar approach: Douglass counters the argument that many slaves tell people who ask that they’re very happy in slavery by telling the story of a young man who’s sold away from his family because he didn’t realize the white man to whom he was complaining about his master was in reality his master (931). And when he mentions Mrs. Auld, the mistress who was kind to him, he makes a comment on the corrupting influence of the institution of slavery:

But, alas! this kind heart had but a short tie to remain such. The fatal poison of irresponsible power was already in her hands, and soon commenced its infernal work. That cheerful eye, under the influence of slavery, soon became red with rage; that voice, made all of sweet accord, changed to one of harsh and horrid discord; and that angelic face gave place to that of a demon (937).

Another aspect of the Narrative, one that sets it apart from other slave narratives, is that it traces the development of Douglass’s mind and spirit. The Narrative’s structure is that of a bildungsroman, a story of the education of a young person, showing how the protagonist grows and struggles as she or he prepares to become a productive member of society. We see Douglass, denied an education because he is a slave, take it upon himself to steal an education, trading food with little white boys for reading lessons (940), learning how to write through observation and trickery (942).

These accomplishments are consistent with what many people consider the central American story: the story of the self-made man, the person who starts out with nothing and through hard work and determination is able to become an accomplished, influential figure. One example would be Benjamin Franklin, a man who starts his life as the youngest son in an impoverished family but is dedicated to improving himself, getting up early in the morning to practice his composition skills, moving to Philadelphia with virtually no money in his pocket and, because of his dedication to hard work, becoming one of the most respected figures in his adopted city.

In the discussion of Whitman, I mentioned the concept of the American Adam, the idea that Americans are unaffected by the forces of history, that Americans have the ability to overcome whatever circumstances they’re born into, that they can create themselves. Douglass is sometimes referred to as “the African-American Benjamin Franklin,” because he starts out with even less than Franklin and because of his hard work and creativity and personal drive is able to become the most influential African American in the nineteenth century. He’s an example of what critics mean when they talk about the American Adam: he can cast off even the powerful forces of slavery and make himself into what he wants to be.

Other critics, of course, would point out that Douglass’s experience contradicts the concept of the American Adam: his achievements are remarkable, but it would be ridiculous to say that he isn’t affected by the forces of history. His life is shaped by the fact that European settlers in America decided to import African slaves for agricultural labor. These critics would argue that Douglass’s experience is evidence that no one escapes from history. This, too, is a significant point. The conversation about whether Americans should have more faith in the past or the future continues to be controversial.

As I’ve already said, one of the qualities that sets Douglass’s Narrative apart from other slave narratives is its presentation of Douglass’s inner development. Douglass’s story of escaping from slavery focuses not just on his outer location but his inner perception. The turning point in his story comes not when he escapes from slavery but when he stands up for himself against the oppression of Mr. Covey, the slave breaker. In introducing the story, Douglass writes, “You have seen how a man was made a slave; you shall see how a slave was made a man” (952). As Mr. Covey is attempting to punish him, Douglass decides to resist and is able to keep Covey from hurting him. He presents this as the most significant achievement of his life:

This battle with Mr. Covey was the turning-point in my career as a slave. It rekindled the few expiring embers of freedom, and revived within me a sense of my own manhood . . . . I felt as I never felt before. It was a glorious resurrection, from the tomb of slavery, to the heaven of freedom. My long-crushed spirit rose, cowardice departed, bold defiance took its place; and I now resolved that, however long I might remain a slave in form, the day had passed forever when I could be a slave in fact (955).

Even though Douglass remains physically in slavery, he no longer thinks like a slave—slavery is not longer his inner reality. One of the consequences of this inner change is that he becomes dedicated to improving the conditions of his fellow slaves: he establishes a school and teaches his fellow slaves how to read. He writes, “I look back to those Sundays with an amount of pleasure not to be expressed. They were great days to my soul. The work of instructing my fellow slaves was the sweetest engagement with which I was ever blessed” (959). Again, this is consistent with a bildungsroman: the process of Douglass’s education involves not just reading and writing but how to be a free man and what he’s going to do with his freedom. Freedom, for Douglass, doesn’t just mean escaping from physical slavery: it involves thinking like a free person and using his freedom to benefit others.

One of the interesting aspects of Douglass’s Narrative is that he presents himself as losing his last vestiges of slavery long after he’s arrived in the North. In the last paragraph of the book, Douglass describes himself as feeling inadequate to address a crowd at an anti-slavery convention:

The truth was, I felt myself a slave, and the idea of speaking to white people weighed me down. I spoke but a few moments, when I felt a degree of freedom, and said what I desired with considerable ease. From that time until now, I have been engaged in pleading the cause of my brethren—with what success, and with what devotion, I leave those acquainted with my labors to decide (975-76).

Notice the way all of these ideas come together. Douglass’s last feelings of being a slave leave as he begins his profession of speaking for his enslaved people. His education has led him up to this point—he has now become what he has been trained to be—and the narrative comes to an end.

For discussion:

- What pro-slavery arguments does Douglass argue against in the Narrative?

- What observations that Douglass makes about slavery strike you as surprising or unexpected?

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home